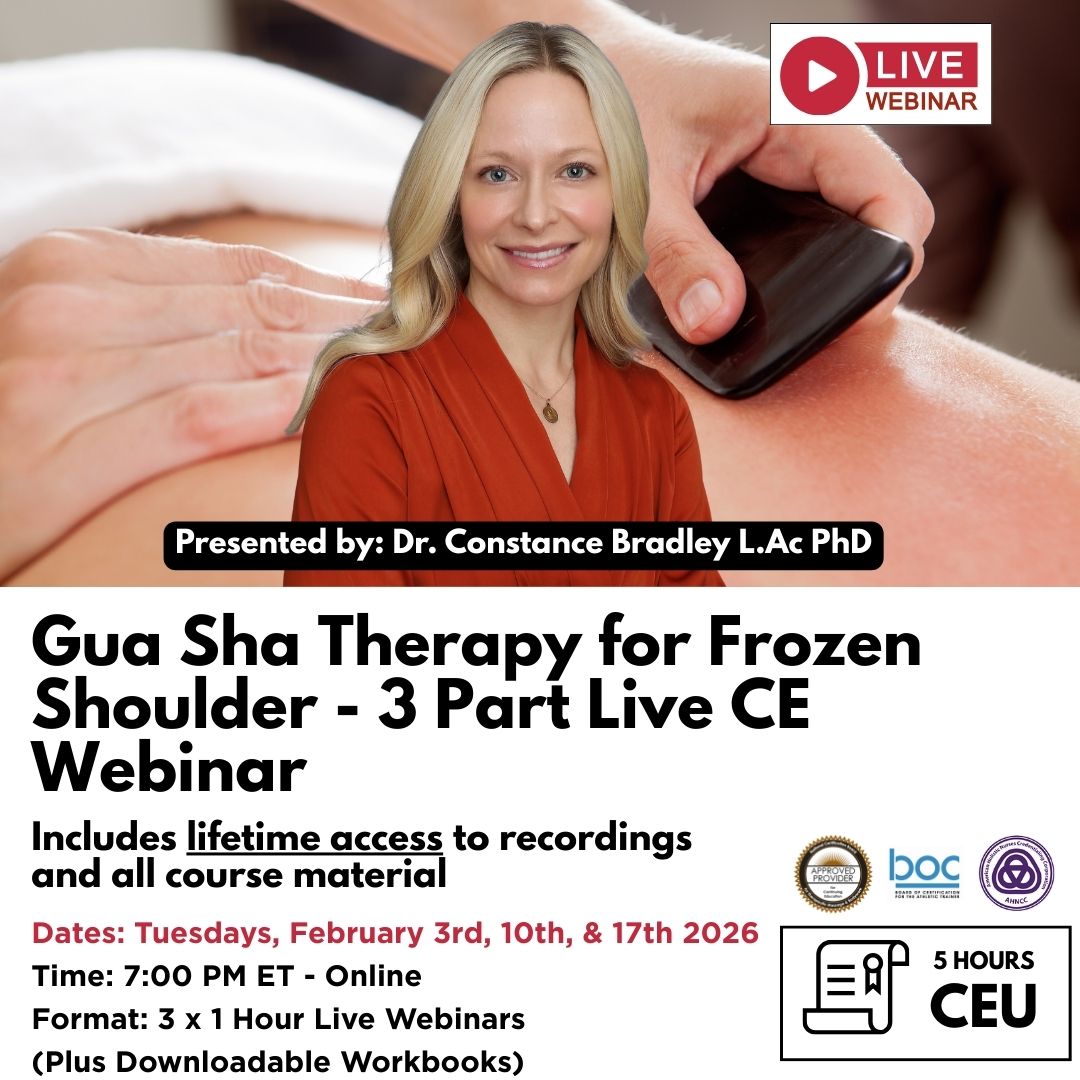

Frozen Shoulder - What is Happening to the Shoulder?

Frozen Shoulder

Frozen Shoulder or Impingement?

Frozen Shoulder Syndrome - What's Going On Inside the Shoulder?

The causes of frozen shoulder syndrome are still poorly understood. About 50% seem to stem from an injury to the shoulder (such as a fall on an outstretched arm) and these are called secondary frozen shoulders.

The other half the time they appear for no apparent reason, and these are called primary frozen shoulders.

Although we don’t know why they happen we do know a lot about what goes on inside the frozen shoulder.

Shoulder Anatomy

The first thing to understand is that the shoulder is a modified ball and socket joint. The ball is at the top of the arm bone (humerus) and the socket is a shallow cup on the end of the scapula (shoulder blade).

This is a good design to give mobility to the shoulder joint but it makes it inherently unstable. To improve the stability of the shoulder, a cuff of four muscles (called the rotator cuff) braces the joint, as well as a complex plethora of tough internal ligaments.

Surrounding the gleno-humeral joint (shoulder joint) is a bag called the capsule. When the arm is raised above the head, this capsule is fully stretched, and when the arm is lowered to the side, the capsule hangs down in a small pouch-like sack (plica).

The synovial capsule contains up to 60ml of synovial fluid. This fluid helps to lubricate the joint and gives the joint surfaces nutrients for repair. Cells lining the joint membrane produce the synovial fluid.

Internal cameras have shown that during the "frozen phase" of a frozen shoulder the capsule may shrink to less than half its normal size!

Sticky Capsule

In frozen shoulder syndrome (adhesive capsulitis), this small sack starts to stick to itself, hence the name of the condition.

As it becomes sticky, the synovial fluid drains away and can often reduce to about 5ml. This makes the joint dry and crackly.

The stickiness is brought on through massive localized inflammation. This inflammation spreads into other shoulder soft-tissues and can cause swelling in other shoulder sacks (bursae).

It has been my experience that this situation may occur the other way around as well. Often a frozen shoulder results from a non-treated biceps tendonitis, or triceps tendonitis.

Both the biceps and triceps tendon run into the ball and socket joint. The tendons, like the muscles, are covered by a clingfilm-like sheath, which gets inflamed and becomes swollen, so the tendon can no longer slide smoothly as the arm is moved.

This quickly leads to a vicious cycle. The tendons become even more swollen and night pain commences.

There is very little free space inside the shoulder joint and all of the tendon sheaths eventually blend together (they are continuous).

This means that thousands of microscopic cells of inflammation can easily make their way from sheath to sheath and eventually the whole shoulder becomes engulfed in a rapid and massive inflammatory cycle.

Inflammation

The nature of inflammation (or swelling) is that it feels worse for rest. This is why the pain is usually worse at night. With even some gentle movement, the swelling typically becomes dissipated and the pain is somewhat reduced.

There are in fact two types of inflammation: acute and chronic. Acute inflammation is the type that happens if you twist your ankle; it rapidly swells then rapidly diminishes over about 72 hours.

If we were to take a sample of the fluid from the ankle and send it to the laboratory, it would have a specific profile of cells. When we see this specific profile we call it acute inflammation.

In the case of frozen shoulder, there is some acute inflammation, but unfortunately a more sinister type of inflammation is also at work. This is called chronic inflammation and it has a different cellular profile.

Chronic Inflammation

The difference is that chronic inflammation lasts a lot longer than 72 hours. In fact, once it has started it seems to fester insidiously for months on end.

As soon as it seems to be getting better, a small setback can trigger the whole process off again in a vicious circle.

Anti-inflammatory drugs are extremely effective at reducing acute inflammation but less good with chronic. This is the same for steroid injections, which block the production of a key ingredient of inflammation called ‘substance P’ (prostaglandin).

This partly explains why tablets and injections have only a limited effect on frozen shoulder syndrome.

Muscle Wasting

With a frozen shoulder, muscle wasting occurs so fast that it cannot possibly be due to lack of use. Other factors are in operation here, and they are more than likely neurological.

This is also the case when someone breaks a bone. When the arm is broken, for example, the muscles waste away within hours. Clearly this is not a result of under-use, it is a neurological phenomenon.

I believe this is all part of the sensory-motor feedback loop. The sensory feedback from the joint is attenuated and as a result the muscles rapidly start to waste away. This is probably the result of an inbuilt protective mechanism.

In the case of a fracture, muscle wasting may occur rapidly so we are forced to avoid putting any weight through the joint. In the case of a frozen shoulder, however, what is a protective mechanism becomes a hindrance, and the arm muscles are held rigid, wasted and useless.

Summary

So if you are suffering from a frozen shoulder, hopefully this will help you understand what is happening inside your shoulder joint. It may all sound depressing but remember that the vast majority of cases can be treated with the NAT treatment protocol.

It's also comforting to know that once you have had it, frozen shoulder rarely comes back again (unless you are one of the 12% who unfortunate enough to get it on the other side).

About Niel Asher Education

Niel Asher Education (NAT Global Campus) is a globally recognised provider of high-quality professional learning for hands-on health and movement practitioners. Through an extensive catalogue of expert-led online courses, NAT delivers continuing education for massage therapists, supporting both newly qualified and highly experienced professionals with practical, clinically relevant training designed for real-world practice.

Beyond massage therapy, Niel Asher Education offers comprehensive continuing education for physical therapists, continuing education for athletic trainers, continuing education for chiropractors, and continuing education for rehabilitation professionals working across a wide range of clinical, sports, and wellness environments. Courses span manual therapy, movement, rehabilitation, pain management, integrative therapies, and practitioner self-care, with content presented by respected educators and clinicians from around the world.

Known for its high production values and practitioner-focused approach, Niel Asher Education emphasises clarity, practical application, and professional integrity. Its online learning model allows practitioners to study at their own pace while earning recognised certificates and maintaining ongoing professional development requirements, making continuing education accessible regardless of location or schedule.

Through partnerships with leading educational platforms and organisations worldwide, Niel Asher Education continues to expand access to trusted, high-quality continuing education for massage therapists, continuing education for physical therapists, continuing education for athletic trainers, continuing education for chiropractors, and continuing education for rehabilitation professionals, supporting lifelong learning and professional excellence across the global therapy community.

Continuing Professional Education

Looking for Massage Therapy CEUs, PT and ATC continuing education, chiropractic CE, or advanced manual therapy training? Explore our evidence-based online courses designed for hands-on professionals.