Winged Scapula: Causes, Symptoms, and How to Address It

Have you ever worked with a client or seen someone whose shoulder blades seem to stick out a little too much, almost like wings on their back? If so, you might have been looking at what’s known as a winged scapula. This condition is more than just a postural quirk—it can lead to pain, weakness, and even difficulty performing everyday tasks. As a manual therapist and athletic trainer, I’ve seen my share of winged scapulas, especially in athletes and people dealing with shoulder injuries. Let’s dive into what this condition is, why it happens, and what can be done about it.

What is a Winged Scapula?

A winged scapula occurs when the shoulder blade (or scapula) doesn’t lie flat against the ribcage but instead juts out. When someone with this condition raises their arm or moves their shoulder blade, you’ll notice the scapula lifting off the back, giving the appearance of a “wing.” While this might look like a minor postural issue, it’s often tied to underlying muscular and neurological problems that can impact shoulder stability and function.

The scapula plays a major role in shoulder health, connecting the arm to the body through the shoulder joint. For smooth, functional movement, the scapula must glide along the ribcage as we lift, reach, or rotate our arms. When the scapula doesn’t sit flat or “winging” occurs, it throws off this movement, making the shoulder unstable. This instability can cause pain, limit range of motion, and lead to a domino effect of problems elsewhere in the shoulder, arm, and even the neck.

Why Does a Winged Scapula Happen?

A winged scapula usually comes down to muscle weakness or nerve damage. The main muscle responsible for keeping the scapula anchored against the ribcage is the serratus anterior. This muscle runs along the side of the chest and attaches to the scapula, playing a key role in pulling it forward and keeping it flush against the ribcage. When the serratus anterior is weak or isn’t firing properly, the scapula can lose its stability, causing it to lift off the ribcage.

The serratus anterior is innervated by the long thoracic nerve, which is crucial in maintaining proper scapular alignment. If this nerve becomes damaged or compressed, it can lead to winged scapula. Long thoracic nerve palsy, or paralysis of the nerve, is a common cause of this condition and can be the result of trauma, repetitive strain, or even surgeries like a mastectomy. In some cases, conditions like viral infections or specific nerve injuries can also affect the nerve, leading to scapular winging.

While the serratus anterior and long thoracic nerve are the usual culprits, other muscles can also contribute to a winged scapula. The trapezius and rhomboid muscles play a role in stabilizing the scapula. If these muscles are weakened or inhibited, such as after an injury, they can also cause the scapula to lose its stable position on the back. This means that a winged scapula isn’t always due to nerve issues alone; it can also result from a more complex interaction of muscles and movement patterns.

The Role of Serratus Anterior Trigger Points in Winged Scapula

The serratus anterior muscle is key to scapular stability, so it’s no surprise that issues in this muscle—whether due to weakness, injury, or trigger points—can play a significant role in developing a winged scapula. Trigger points are small, tender areas within a muscle that can cause pain, restrict movement, and weaken the affected muscle. In the case of the serratus anterior, trigger points can either develop as a result of the muscle’s constant struggle to keep the scapula stable, or they may arise due to improper body mechanics, repetitive strain, or an underlying injury.

When trigger points form in the serratus anterior, they disrupt the muscle’s ability to contract properly and hold the scapula against the ribcage. Essentially, trigger points make the serratus anterior less efficient at stabilizing the scapula, which increases the likelihood of winging. As a result, people with a winged scapula may experience tightness, aching, or even sharp pain along the side of the ribcage, around the shoulder blade, or into the shoulder itself.

Trigger points in the serratus anterior can sometimes be both a symptom and a cause of winged scapula. For example, if an individual develops a winged scapula due to poor posture or nerve dysfunction, the serratus anterior may become strained as it works overtime to keep the scapula stable. Over time, this overuse can lead to trigger points in the muscle, further weakening it and perpetuating the cycle of scapular instability. Similarly, if the serratus anterior is already compromised by trigger points, it may not have the strength or endurance to properly stabilize the scapula, leading to winging.

Signs and Symptoms of a Winged Scapula

One of the telltale signs of a winged scapula is, of course, the appearance of the scapula lifting away from the back, especially when lifting the arms or pressing against a wall. But beyond the visual cue, people with a winged scapula often experience other symptoms that affect shoulder health and daily function.

Pain is a common complaint, particularly around the shoulder blade and along the shoulder itself. Because the scapula isn’t functioning correctly, the shoulder joint becomes less stable, causing discomfort and even sharp pain with certain movements. Over time, this instability can lead to shoulder impingement or rotator cuff issues, as the muscles and tendons around the shoulder are forced to compensate for the lack of stability.

People with a winged scapula might also notice weakness in the shoulder, especially when trying to lift objects overhead or push against resistance. Simple tasks, like reaching for something on a high shelf, can become challenging. In more severe cases, the condition can even limit the range of motion, making it hard to perform normal activities without discomfort.

Another symptom that people often overlook is neck pain. Since the shoulder blade isn’t sitting correctly, the muscles around the neck and upper back—like the upper trapezius—may have to work harder to support and move the shoulder. This extra strain can lead to tension and pain in the neck and upper back, creating a cycle of discomfort that’s hard to break without proper intervention.

How is a Winged Scapula Diagnosed?

If you suspect a winged scapula, it’s important to get a thorough evaluation to determine the exact cause. Diagnosing a winged scapula involves both physical examination and, in some cases, imaging studies or nerve tests. A physical exam is often the first step, where a healthcare provider might ask the person to push against a wall with their arms outstretched, a simple test that often reveals the winging of the scapula.

During the physical exam, a therapist or physician will likely look for signs of muscle weakness or asymmetry and may assess shoulder mobility and function. If nerve involvement is suspected, such as with long thoracic nerve palsy, nerve conduction studies or electromyography (EMG) might be performed to evaluate nerve function. Imaging studies, like an MRI, can sometimes provide additional insight into any soft tissue damage or inflammation that could be contributing to the winging.

It’s also crucial to rule out other potential causes of shoulder instability. Conditions like rotator cuff tears, shoulder impingement, or labral injuries can sometimes mimic the symptoms of a winged scapula, so a thorough assessment is essential to ensure accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Treatment Options for Winged Scapula

Treating a winged scapula often involves a multi-faceted approach that combines physical therapy, strengthening exercises, and sometimes, in more severe cases, surgical intervention. The goal of treatment is to restore stability to the scapula, improve shoulder function, and relieve any pain associated with the condition.

Physical therapy is typically the cornerstone of treatment for a winged scapula. A physical therapist will create a program tailored to strengthen the serratus anterior and other muscles that support the scapula. Exercises that target scapular stability are essential, focusing on activating the serratus anterior and improving the overall function of the shoulder girdle. Movements like wall slides, scapular push-ups, and resisted punches can help re-engage the serratus anterior, encouraging it to pull the scapula back against the ribcage.

Addressing serratus anterior trigger points can also be highly effective. Techniques like trigger point therapy or dry needling may be used to release the muscle knots and restore proper function to the serratus anterior. A therapist might apply steady pressure to the trigger points or use myofascial release techniques to relieve tension. Once the trigger points are released, clients often notice an improvement in scapular stability and a reduction in pain.

Since poor posture can exacerbate a winged scapula, addressing posture is an important part of treatment. Many people with winged scapula have rounded shoulders or forward head posture, which can further destabilize the shoulder. Exercises and stretches that open up the chest and bring the shoulder blades back are helpful. This can include pec stretches, upper back strengthening, and posture-focused movements like scapular retractions.

For clients dealing with nerve-related winging, neuromuscular re-education is an essential part of therapy. This involves retraining the nervous system and muscles to work together more effectively, using techniques that help the brain reconnect with the muscles that need activation. Often, therapists will incorporate tactile cues or use resistance bands to help clients “feel” the movement and develop better motor control over the shoulder.

In severe cases where there’s significant nerve damage or where conservative treatments haven’t been effective, surgery may be considered as a last resort. Surgical options may include nerve transfer or muscle transfers to restore function to the scapula. However, surgery is a complex decision, and it requires a significant commitment to post-operative rehabilitation.

Preventing Winged Scapula and Maintaining Shoulder Health

Preventing a winged scapula often comes down to maintaining good posture, avoiding overuse, and keeping the shoulder muscles balanced. Athletes and people who frequently perform overhead activities should focus on regular strength training, with particular attention to the shoulder stabilizers. Keeping the rotator cuff, serratus anterior, and upper back muscles strong can reduce the likelihood of scapular winging and improve overall shoulder stability.

Additionally, taking breaks and modifying activities can help prevent overuse injuries that might contribute to scapular dysfunction. For example, if you’re someone who spends hours lifting weights or performing repetitive movements, it’s essential to incorporate rest and vary your exercises to avoid overstressing any single muscle group.

If you start to notice any signs of shoulder instability or discomfort around the scapula, addressing it early can prevent the problem from worsening. Working with a physical therapist or trainer who understands shoulder biomechanics can provide guidance and exercises tailored to keep the scapula stable and supported.

Final Thoughts on Winged Scapula

A winged scapula might seem like a minor issue, but it can have a significant impact on shoulder function and quality of life. By understanding what causes scapular winging, recognizing the symptoms, and taking the right steps to address it, people can regain control over their shoulder health and reduce pain and instability.

With the right mix of physical therapy, strengthening exercises, and postural correction, most cases of winged scapula can be managed effectively without the need for invasive interventions. And for those dealing with nerve damage or more severe cases, there are still options available to restore stability and function to the shoulder.

Whether you’re an athlete, a manual therapist, or someone experiencing shoulder discomfort, knowing about winged scapula can be valuable. It’s one of those conditions that, when understood and treated appropriately, can make a world of difference in how we move, lift, and live pain-free.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and should not replace medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult a qualified healthcare provider for any shoulder pain or related issues.

References

- Warner, J. J., et al. (1998). "The Etiology of Scapular Winging." Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery.

- Kibler, W. B., et al. (2006). "Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain." Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

- Martin, R. M., & Fish, D. E. (2008). "Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments." Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine.

About Niel Asher Education

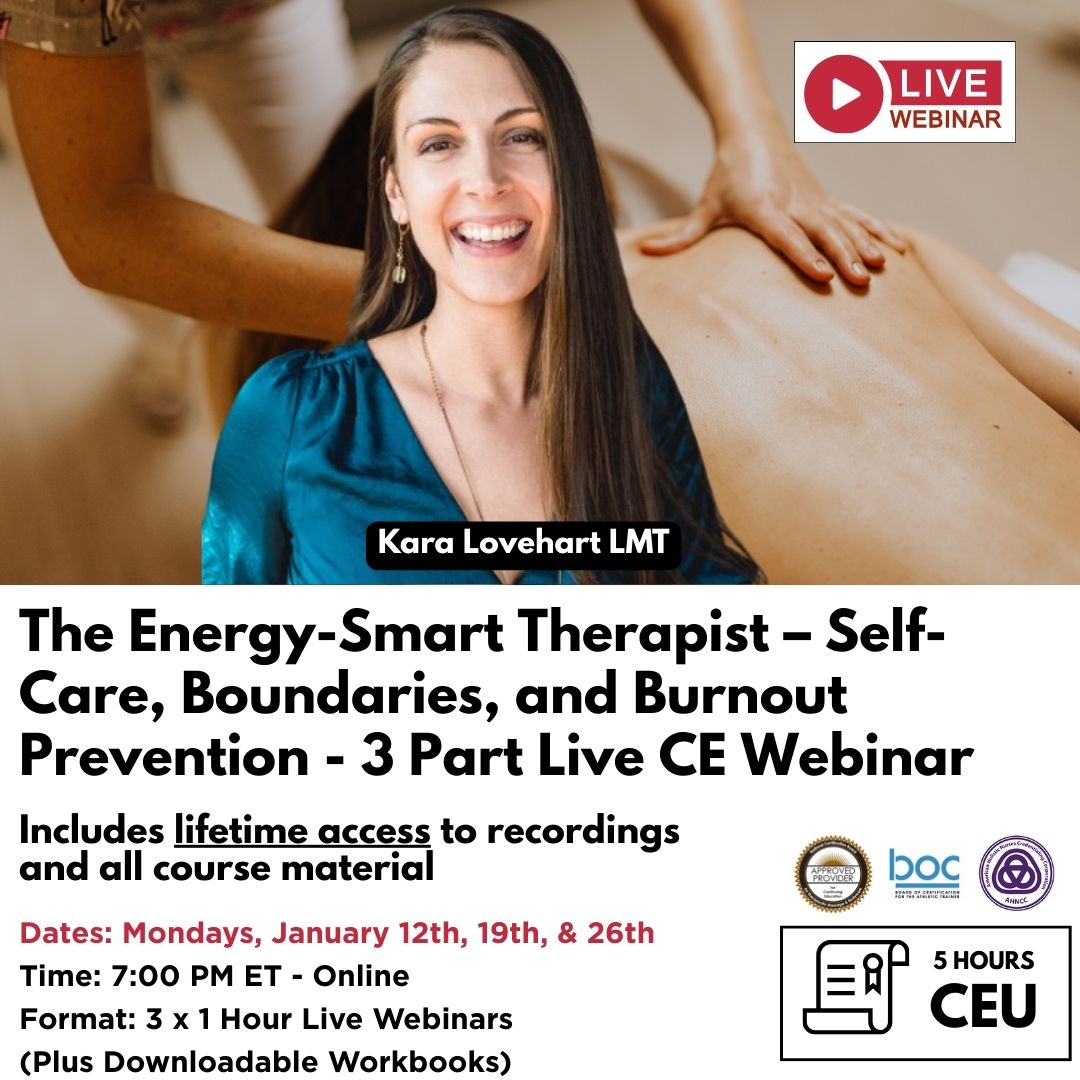

Niel Asher Education (NAT Global Campus) is a globally recognised provider of high-quality professional learning for hands-on health and movement practitioners. Through an extensive catalogue of expert-led online courses, NAT delivers continuing education for massage therapists, supporting both newly qualified and highly experienced professionals with practical, clinically relevant training designed for real-world practice.

Beyond massage therapy, Niel Asher Education offers comprehensive continuing education for physical therapists, continuing education for athletic trainers, continuing education for chiropractors, and continuing education for rehabilitation professionals working across a wide range of clinical, sports, and wellness environments. Courses span manual therapy, movement, rehabilitation, pain management, integrative therapies, and practitioner self-care, with content presented by respected educators and clinicians from around the world.

Known for its high production values and practitioner-focused approach, Niel Asher Education emphasises clarity, practical application, and professional integrity. Its online learning model allows practitioners to study at their own pace while earning recognised certificates and maintaining ongoing professional development requirements, making continuing education accessible regardless of location or schedule.

Through partnerships with leading educational platforms and organisations worldwide, Niel Asher Education continues to expand access to trusted, high-quality continuing education for massage therapists, continuing education for physical therapists, continuing education for athletic trainers, continuing education for chiropractors, and continuing education for rehabilitation professionals, supporting lifelong learning and professional excellence across the global therapy community.

Continuing Professional Education

Looking for Massage Therapy CEUs, PT and ATC continuing education, chiropractic CE, or advanced manual therapy training? Explore our evidence-based online courses designed for hands-on professionals.