Trigger Points - Digastric Muscle, TMD and Jaw Pain

Tempromandibular Joint Dysfunction

Tempromandibular joint dysfunction (TMD), a disorder of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), is a common condition affecting a large percentage of adults. The condition affects the muscles and joints of the jaw. This disorder may result from an injury to the jaw bone, or it may be caused by an underlying medical condition.

The TM joint connects the jaw to the skull. The two parts of the joint may be dislocated due to trauma, or the soft interior discs that cushion the joint may slip out of place. TMJ disorders are common and can result in pain and dysfunction in the jaw, face, and head. Some disorders can be treated with simple therapies, while others may require surgery.

The condition is more common in women than men, but both sexes are at risk of developing TMDs. The condition can be caused by dental trauma, bruxism, or stress. The most common symptom of TMD is jaw pain. It can also cause facial pain and headache. The pain may occur for a short period of time or may be persistent. If it is persistent, the condition can cause significant structural damage to the jaw joint.

Many people who experience TMDs have no idea why they are experiencing pain. In other cases, the condition may begin with no apparent cause. It may be triggered by bruxism, a disorder where people grind their teeth at night. Other symptoms can include a decreased range of motion in the mandible, pain in the periauricular area, and a clicking or popping sound while chewing or speaking. In rare cases, the pain can be caused by arthritis of the joint.

There are three FDA-approved TMJ implants. These implants are placed in the jaw joint to help with TMJ dysfunction. They are available at dental offices across the United States. The use of these implants has been approved by the FDA as an alternative to open surgery.

Symptoms of TMJ dysfunction include pain in the jaw and face, a clicking or popping sound while chewing, and a decreased range of motion in the mandible. If you experience symptoms of TMJ dysfunction, your doctor may order imaging of the TM joint. An arthroscopy is a type of surgery that involves insertion of a small video camera into the jaw joint. The camera will allow the surgeon to see the joint and reposition the disc. In addition to repositioning the disc, an arthroscopy may be used to remove any adhesions in the joint.

Symptoms of TMJ dysfunction can occur for a short period of time, or may occur in conjunction with another medical condition. Many people who have TMJ dysfunction also experience headaches. Some inflammatory disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, may affect the TMJ. A traumatic injury to the jaw bone, such as during a car accident, may also cause TMJ pain. A physical examination should include palpation of the masticatory muscles. The jaw may be open when the masticatory muscles are palpated. The jaw should be opened at least 35 to 45 millimeters (mm). If the opening is less than 25 mm, it is a sign of dysfunction.

Manual Therapy for TMD

Symptoms of TMD include pain, locking, popping, and discomfort in the jaw, neck, or neck and head pain. Symptoms may develop at random or may appear in a larger segment of the population, and can have no obvious medical cause. TMD can be managed with physical therapy. It may include exercises, massage, electro-galvanic stimulation, and thermal modalities.

Manual therapy is the application of a small amount of force to soft tissue structures. It may be performed by hand, a hand-held instrument, or by an electro-therapy device. The goal of manual therapy is to relieve discomfort, reduce pain boundary, and restore normal function of the TMJ. However, manual therapy can be painful. The biggest risk is that it can aggravate existing pain. In addition, it can take time to get the best results. In some cases, manual therapy may involve the use of advanced technology, such as cold lasers.

In a systematic review by Calixtre et al, the authors evaluated the evidence of manual therapy for the treatment of TMD. They used the Cochrane risk of bias tool to evaluate the risk of bias for eligible trials. Several RCTs were found, but the overall quality of the evidence was low. Those trials with low or unclear risk of bias were considered high quality, and those with high or unclear risk of bias were considered poor quality. These RCTs included physical therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and relaxation techniques. The researchers found that physical therapy improved the resting position of the jaw and neck. In addition, cognitive-behavioral therapy improved long-term outcomes for TMD patients.

In addition, they reviewed published articles on genetic factors that may affect TMD. They found that the majority of studies reported low effect sizes. They concluded that there is no high quality evidence to support the use of manual therapy for TMD. The authors also found that no studies addressed the biologic reasons for mandibular repositioning procedures. However, they found two papers that met the study inclusion criteria. These papers included the use of trigger point dry needling to treat neuromusculoskeletal pain and the use of intra-oral appliances for headaches.

Another study, by Oliveira et al, evaluated the effectiveness of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of TMD. The investigators evaluated the effects of tDCS on pain and dysfunction, as well as quality of life. They found that tDCS provided promising results, especially in combination with exercises. However, the investigators reported low sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios. They also found contradictory predictive values. They concluded that tDCS has limited value for the treatment of TMD.

Anatomy

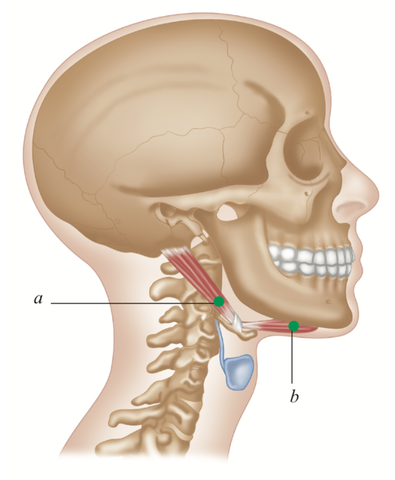

Anterior belly: digastric fossa on inner side of lower border of mandible, near symphysis. Posterior belly: mastoid notch of temporal bone.

Several anatomists and physicians have recorded morphological and functional variations of the digastric muscle. This muscle, which is a key muscle of the neck, connects the hyoid bone to the mandible. It opens the mouth and assists in swallowing. These variations are important in clinical practice and can help avoid unnecessary surgical procedures. They can also help in planning treatment.

The digastric muscle is a small paired muscle of the neck. It consists of an anterior belly and a posterior belly. The anterior belly is innervated by the facial nerve. It contains the mylohyoid branch of the inferior alveolar artery. The posterior belly is supplied by the vagus nerve and the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves. Its origin is derived from different embryological precursors.

The anterior belly of the digastric muscle is more likely to have varying origins and insertions. It is also more likely to have bilateral variations. Its insertions can vary from midline raphe to mylohyoid muscle. In addition, it can be angularly decreased in volume. This can lead to excessive bulging of the anterior neck. In addition, the muscle is commonly injured by teeth grinding, sprains, and overuse. It can also be injured by clenching the jaw.

The intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle is encircled by a fibrous tissue sling, which acts as a pulley. The sling allows the muscle to slide easily. The intermediate tendon is innervated by the mylohyoid nerve and the facial nerve. In addition, the sling is anchored on the superior side of the hyoid bone.

The posterior belly of the digastric muscle originates from the medial surface of the mastoid notch of the temporal bone. It then passes deep to the hyoid bone and pierces the stylohyoid muscle. It also contains the facial nerve, the vagus nerve, and the anterior jugular vein.

The posterior belly of the digastric is most closely related to the neurovascular bundle of the neck. It also contains the submandibular lymph nodes and the internal and external carotid arteries. In addition, it contains the submandibular gland and submental lymph nodes. The muscle is also innervated by the facial nerve.

Variations of the digastric muscle can be categorized by gender, presentation type, and ethnicity. They can be analyzed according to these categories and presented with figures. This can help physicians in the diagnosis and treatment planning process.

The prevalence of digastric muscle variations is found to be higher in the Asian population. However, they are not necessarily associated with clinical symptoms. In addition, physicians need to know the normal anatomy of the digastric muscle to help in the diagnosis and treatment of patients.

Trigger Points and Referred Pain

a) Posterior, b) Anterior

Insertion

Body of hyoid bone via a fascial sling over an intermediate tendon.

Action

Raises hyoid bone. Depresses and retracts mandible as in opening the mouth.

Nerve

Anterior belly: mylohyoid nerve, from trigeminal V nerve (mandibular division).

Posterior belly: facial (V11) nerve.

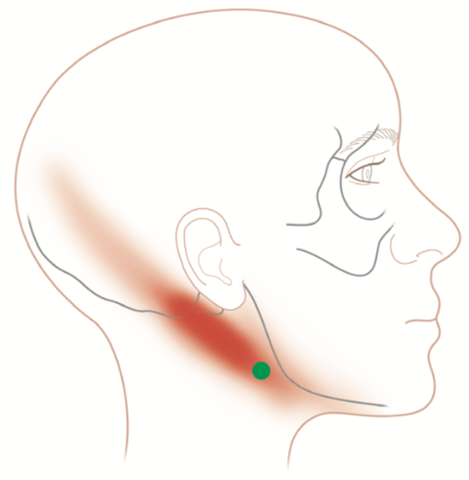

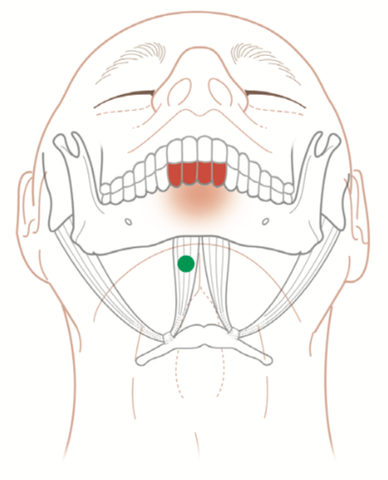

Posterior: strong 2 cm zone around mastoid and vaguely the zone to chin and throat, occasionally to scalp.

Indications

Throat pain, dental pain (four lower incisors), headache, jaw pain,

renal tubular acidosis, prolonged/ extensive dental work (blurred vision and dizziness), lower mouth opening, difficulty swallowing, vocal/singing problems.

Causes

Head-forward/upper crossed

pattern, poor bite mechanics and/

or clenching/grinding of teeth (bruxism), whiplash, telephone to chin, musical instruments (e.g. violin or wind instruments).

Differential Diagnosis

Dental problems—malocclusion. Hyoid bone. Thyroid problems. Thymus gland. Sinusitis. Carotid artery.

Connections

SCM, sternothyroid, mylohyoid, stylohyoid, longus colli/capitis, geniohyoid, cervical vertebrae, temporalis, masseter.

General Self Help:

Bite Plates/Blocks/ Occlusal Splints

Opinion varies as to efficacy, type, and duration of use for occlusal devices. An evidence base suggests they can be beneficial.

Advice

Breathing patterns. Bruxism. Head postures.

Posture

Head forward or upper crossover patterns can be treated by a range of manual and trigger point therapists.

This trigger point therapy blog is intended to be used for information purposes only and is not intended to be used for medical diagnosis or treatment or to substitute for a medical diagnosis and/or treatment rendered or prescribed by a physician or competent healthcare professional. This information is designed as educational material, but should not be taken as a recommendation for treatment of any particular person or patient. Always consult your physician if you think you need treatment or if you feel unwell.

About Niel Asher Education

Niel Asher Education (NAT Global Campus) is a globally recognised provider of high-quality professional learning for hands-on health and movement practitioners. Through an extensive catalogue of expert-led online courses, NAT delivers continuing education for massage therapists, supporting both newly qualified and highly experienced professionals with practical, clinically relevant training designed for real-world practice.

Beyond massage therapy, Niel Asher Education offers comprehensive continuing education for physical therapists, continuing education for athletic trainers, continuing education for chiropractors, and continuing education for rehabilitation professionals working across a wide range of clinical, sports, and wellness environments. Courses span manual therapy, movement, rehabilitation, pain management, integrative therapies, and practitioner self-care, with content presented by respected educators and clinicians from around the world.

Known for its high production values and practitioner-focused approach, Niel Asher Education emphasises clarity, practical application, and professional integrity. Its online learning model allows practitioners to study at their own pace while earning recognised certificates and maintaining ongoing professional development requirements, making continuing education accessible regardless of location or schedule.

Through partnerships with leading educational platforms and organisations worldwide, Niel Asher Education continues to expand access to trusted, high-quality continuing education for massage therapists, continuing education for physical therapists, continuing education for athletic trainers, continuing education for chiropractors, and continuing education for rehabilitation professionals, supporting lifelong learning and professional excellence across the global therapy community.

Continuing Professional Education

Looking for Massage Therapy CEUs, PT and ATC continuing education, chiropractic CE, or advanced manual therapy training? Explore our evidence-based online courses designed for hands-on professionals.